Edit, edit, edit

How British designer Lou Dalton is making her name in menswear

In 2009, a fiery young Brit left a career as an in-house designer in high fashion and put her experience and impressive resumé into a new venture, creating her own eponymous label and catching the attention of the British Fashion Council in the process.

Today, Lou Dalton shows her menswear collection at London Fashion Week and is carried by some of the best retailers in the world, including Dover Street Market, Grenson, and Opening Ceremony.

To learn more, we sat down with Dalton to talk about the path to starting her own label, the struggles of dealing with an international retail landscape, and her relentless obsession with sweating the details.

How did you get started?

I left school at 16 to work for a bespoke tailor back in my hometown in the UK. I come from a little place called Stoke upon Tern. I enrolled in an apprenticeship and that’s when I was introduced into working predominantly in menswear.

When I came back to London, I worked as a jobbing designer from high street to high fashion and worked a lot with Japanese companies. I’d design something and then have to get it produced, and the production had to be within the UK or the British Isles. I was introduced to all the manufacturing support within the British Isles, from knitwear and footwear, to ready-to-wear apparel, which is what we do. That was a massive insight, so from there I kind of started evolving the idea that I’d have my own brand and then in 2009 I launched Lou Dalton.

To backtrack a bit, when you dropped out of school, were you still living at home?

Were your parents supportive of the idea?

From a lack of interest?

I began to realize that I wasn’t that stupid, that I had a gift, and it was really honing in on what my strength was. Because menswear was at the forefront of what I was being involved with, it was a given that it was what I was going to do.

I’m not really a girl-girl. I love a red lip and I love a heel, but everything I do has always had a very androgynous thing. I’ve always felt very menswear oriented. I know menswear better than most men, probably because I come from a very good construction and tailoring background so I understand the male form very well.

How long have you been designing your own collection?

Do you have any specific examples?

You have to be careful, especially when the exchange rate is so crippling, and we’ve suffered at times because of that. So I’ve become very aware about how I can change the dynamic of Lou Dalton so that we can hopefully bring these stores back on board without changing who we are and being very clear about what our aesthetic is.

How much of your business is international, where it is affected by the dollar?

A great example: last season and the A/W 15 collection. I was very proud because it felt like we finally started to shape up who we were as a brand and what I stood for, which was [being] obsessed with details. I’m obsessed with the finish. I’m obsessed with construction and the engineering behind a garment and how that reflects on the male form. But it was too expensive. We had a great store in Japan who we were selling to along with Dover Street Market, but it was too expensive for them and they took a season back and it was crippling. This season they came back because we re-evaluated everything.

After re-evaluating, are there any sacrifices that you’ve made?

I might as well go home now and just not do it anymore because I don’t want to give you just market fodder. I want to give you something beautiful that you want to be inspired to wear and that you want to look at every season. You want to log on and see what Lou Dalton is doing every season, and that’s why it’s really important.

I want to be in here for the long haul and I’ll do everything and fight tooth and nail to keep it going so I had to [re-align the pricing with the collection]. It was a challenge, but it was one that I was prepared to do and I don’t feel like I’ve sacrificed anything along the way.

Do you find pricing constrains the creative process or does it help being out there, hands-on, sourcing fabrics and thinking of different ways of achieving the look you’re aiming for?

I don’t want to have to cut down on the Lou Dalton aesthetic or what I believe is our strength, but I appreciate that sometimes I have to carefully edit so we can produce the same jacket in three different fabrics and tell three different stories.

I appreciate how you mention the editing. It’s something that so many people struggle with early on. Is that something you think you’ve improved upon?

To give our readers a more concrete visual, how much smaller is the S/S16 collection compared to A/W15?

Do you find that narrowing things down helps the audience, not only your core fanbase and customers but everyone, identify items as a Lou Dalton piece?

Absolutely, we get that feedback. I don’t change the blocks every season. I don’t redesign the wheel in terms of the actual shirt block or the trouser block because we are a small brand so you do want to build a client base where you become familiar. You want to have that continuity so I try to hone in on that.

Is there any sort of internal conflict in terms of where the feedback comes from, i.e. press vs. retailers?

Can you think of any lessons that you wish you knew at 19 or as a junior designer?

Part of me as well, when there are people doubting you and are quick to judge what you do, you get a bit between your teeth to prove them wrong. I feel relevant as a brand and that we have something different to say.

The day I feel that has stopped and I have to dilute [what I do] so that it’s unrecognizable, then I’ll go and get a full-time job and do it for Gap for God’s sake. If I’m going to rip something back that there’s no heart and soul in it, I might as well be a jobbing designer.

I feel that having a bit of a knock sometimes can bring you back to where you needed to be and make you hone in on what and who you are and I think that’s exactly what we’ve done this time.

What do you want Lou Dalton to be recognized for?

I do believe there is a market for somebody like Lou Dalton and what we’re doing to really own it. It’s great fabric and great detail at a great price – not cheap by any means but good value. You’re getting value for money and I think that’s what is really important.

In 2009, a fiery young Brit left a career as an in-house designer in high fashion and put her experience and impressive resumé into a new venture, creating her own eponymous label and catching the attention of the British Fashion Council in the process.

Today, Lou Dalton shows her menswear collection at London Fashion Week and is carried by some of the best retailers in the world, including Dover Street Market, Grenson, and Opening Ceremony.

To learn more, we sat down with Dalton to talk about the path to starting her own label, the struggles of dealing with an international retail landscape, and her relentless obsession with sweating the details.

How did you get started?

I had always been inspired and obsessed with fashion from an early age. My grandmother had a real strong sense of fashion, and she always had a hat and shoe for every occasion. I was kind of always obsessed with that, but I didn’t really know at the time where I wanted to take my career.

I left school at 16 to work for a bespoke tailor back in my hometown in the UK. I come from a little place called Stoke upon Tern. I enrolled in an apprenticeship and that’s when I was introduced into working predominantly in menswear.

I'm not really a girl-girl. I love a red lip and I love a heel, but everything I do has always had a very androgynous thing. I’ve always felt very menswear oriented. I know menswear better than most men.When I enrolled in the actual apprenticeship, it became apparent that menswear was my thing, and I realized at the time that if I really wanted to take [my career] further and make it into something, I would need to go back into education. After three years as an apprentice, I enrolled back in school and graduated with a Master’s of Design from the Royal College of Arts in London. Upon graduating, I moved straight to Italy where I worked as a junior designer at brands such as Stone Island and so forth.

When I came back to London, I worked as a jobbing designer from high street to high fashion and worked a lot with Japanese companies. I'd design something and then have to get it produced, and the production had to be within the UK or the British Isles. I was introduced to all the manufacturing support within the British Isles, from knitwear and footwear, to ready-to-wear apparel, which is what we do. That was a massive insight, so from there I kind of started evolving the idea that I'd have my own brand and then in 2009 I launched Lou Dalton.

To backtrack a bit, when you dropped out of school, were you still living at home?

Yes, I left school with very few qualifications.

Were your parents supportive of the idea?

If I didn't go to school, my folks would get into trouble so I just sat through it. I didn’t particularly do very well. I did very well in art and textiles and English. In pretty much everything else, I just managed to scrape through.

From a lack of interest?

Yeah, when I went through this [apprenticeship] working environment, working for somebody where I saw an end result. It gave me such a huge amount of self-respect, it felt like I was doing something and it was probably the best education I ever had. I gained respect for others, it was on my terms, and I felt like I was achieving more.

I began to realize that I wasn't that stupid, that I had a gift, and it was really honing in on what my strength was. Because menswear was at the forefront of what I was being involved with, it was a given that it was what I was going to do.

I'm not really a girl-girl. I love a red lip and I love a heel, but everything I do has always had a very androgynous thing. I’ve always felt very menswear oriented. I know menswear better than most men, probably because I come from a very good construction and tailoring background so I understand the male form very well.

How long have you been designing your own collection?

I’ve been around for a while. Messing around with it. But it was in 2009 that I got support from the British Fashion Council and people started to really take note of what we were doing. There have been peaks and troughs and I'm no longer the new kid on the block and such, but it’s [about] maintaining the interests. Sometimes when things start to dip a little bit, you have to really look at your business model and think, “How are we going to change that? What can we do to try and keep the interest?” Keep people like [media] coming along to see what we're doing.

Do you have any specific examples?

I realized that within retail, the industry has changed so much over the last two years, the consumer wants more for his buck, and pricing is very difficult for certain brands. Even on the top end, people like Dries Van Noten and Raf Simons have had to bring their pricing down, and when you’re a brand that doesn’t advertise, you can’t warrant the garment - a shirt or something - for £300 [about US$600]. That’s a lot of money.

You have to be careful, especially when the exchange rate is so crippling, and we’ve suffered at times because of that. So I’ve become very aware about how I can change the dynamic of Lou Dalton so that we can hopefully bring these stores back on board without changing who we are and being very clear about what our aesthetic is.

How much of your business is international, where it is affected by the dollar?

Now it's fair to say we've got a good footing in the door internationally. This season alone [SS16], we've just finished with Paris. We actually saw [growth] more, especially in Japan and in the Asian markets.

A great example: last season and the A/W 15 collection. I was very proud because it felt like we finally started to shape up who we were as a brand and what I stood for, which was [being] obsessed with details. I'm obsessed with the finish. I'm obsessed with construction and the engineering behind a garment and how that reflects on the male form. But it was too expensive. We had a great store in Japan who we were selling to along with Dover Street Market, but it was too expensive for them and they took a season back and it was crippling. This season they came back because we re-evaluated everything.

After re-evaluating, are there any sacrifices that you've made?

I'm obsessed with cloth and I would quite happily produce everything on these four rails with £50/m fabric, but it’s not realistic. I have to spend time sourcing something that can do the same job as that beautiful piece of cashmere, look as amazing as that for something like £10/m, which means that I can fulfill my aesthetic without compromise, because the minute I have to do that I'm just going to pack up and say bugger it.

I might as well go home now and just not do it anymore because I don’t want to give you just market fodder. I want to give you something beautiful that you want to be inspired to wear and that you want to look at every season. You want to log on and see what Lou Dalton is doing every season, and that’s why it’s really important.

I want to be in here for the long haul and I'll do everything and fight tooth and nail to keep it going so I had to [re-align the pricing with the collection]. It was a challenge, but it was one that I was prepared to do and I don’t feel like I’ve sacrificed anything along the way.

Do you find pricing constrains the creative process or does it help being out there, hands-on, sourcing fabrics and thinking of different ways of achieving the look you're aiming for?

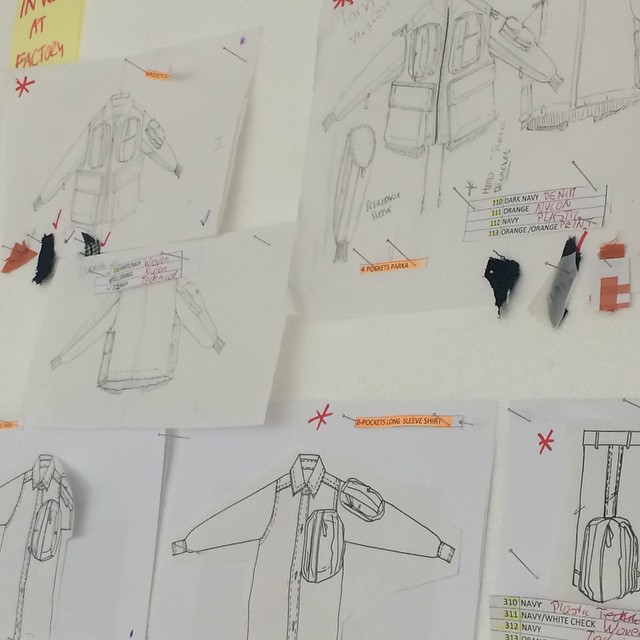

When we started the big coats here, they had so many internal pockets, everything but the kitchen sink. What I learned from this is I start off with the design that I want, and what I have to do then is edit and edit so that the exterior of it looks exactly like that sketch on the wall, but I streamline the internal construction so that I'm not compromising the design because I just don't want to have to do that.

I don't want to have to cut down on the Lou Dalton aesthetic or what I believe is our strength, but I appreciate that sometimes I have to carefully edit so we can produce the same jacket in three different fabrics and tell three different stories.

I appreciate how you mention the editing. It’s something that so many people struggle with early on. Is that something you think you've improved upon?

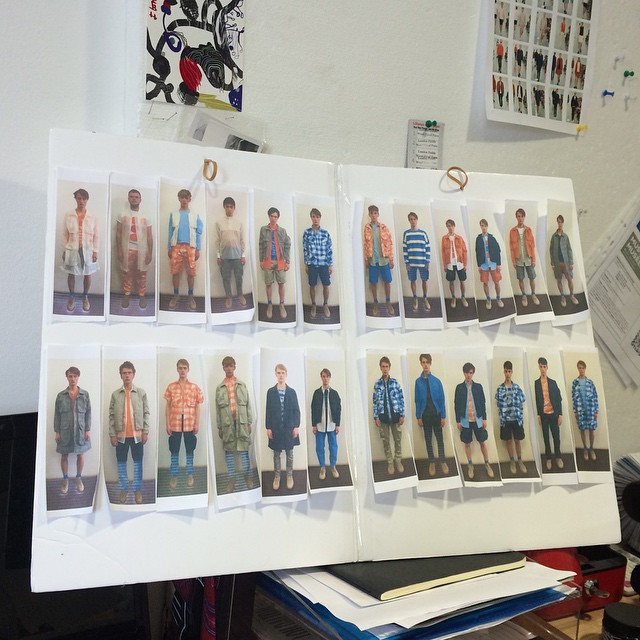

This is the first season we really did edit, because with A/W - as much it will go down as one of my favorite collections of all time - I didn’t edit anything. We ended up with six racks of clothes, ridiculous amounts of options, and as a buyer you've got too much to buy into. This season it was really edit, edit, edit.

To give our readers a more concrete visual, how much smaller is the S/S16 collection compared to A/W15?

In this collection we double up on lots of things, A/W was something like 80 to 90 pieces and then this collection, it was like 70 pieces. It was a lot less and felt far more focused, really honing in on what has been selling for us.

Do you find that narrowing things down helps the audience, not only your core fanbase and customers but everyone, identify items as a Lou Dalton piece?

Absolutely, we get that feedback. I don't change the blocks every season. I don't redesign the wheel in terms of the actual shirt block or the trouser block because we are a small brand so you do want to build a client base where you become familiar. You want to have that continuity so I try to hone in on that.

Is there any sort of internal conflict in terms of where the feedback comes from, i.e. press vs. retailers?

Retail is key more than anything. I totally respect the press and we need them on board. The minute the show has gone out, we all live to see what the review is on Style.com [now Vogue.com]. It's the first thing folks look at. Sometimes you do feel it can make or break you, and the reviews are really key because the buyers do tend to look at that, but it’s the buyer that will keep Lou Dalton in business, not the press, unfortunately.

Can you think of any lessons that you wish you knew at 19 or as a junior designer?

I think you can always say “Oh if only,” but I think you have to make mistakes to come out on the other side.

Part of me as well, when there are people doubting you and are quick to judge what you do, you get a bit between your teeth to prove them wrong. I feel relevant as a brand and that we have something different to say.

The day I feel that has stopped and I have to dilute [what I do] so that it's unrecognizable, then I'll go and get a full-time job and do it for Gap for God's sake. If I'm going to rip something back that there's no heart and soul in it, I might as well be a jobbing designer.

I feel that having a bit of a knock sometimes can bring you back to where you needed to be and make you hone in on what and who you are and I think that's exactly what we've done this time.

What do you want Lou Dalton to be recognized for?

I want it to be a successful, ready-to-wear menswear line, to be here when I'm not here. To have that legacy. Great attention to detail and fabric, and something that the man on the street would want to wear.

I do believe there is a market for somebody like Lou Dalton and what we're doing to really own it. It's great fabric and great detail at a great price - not cheap by any means but good value. You're getting value for money and I think that’s what is really important.